This is your brain on writing

What happens in the brain of a writer during the creative process is fascinating. In a follow-up to his article about reading, our curious author explores what makes writers unique.

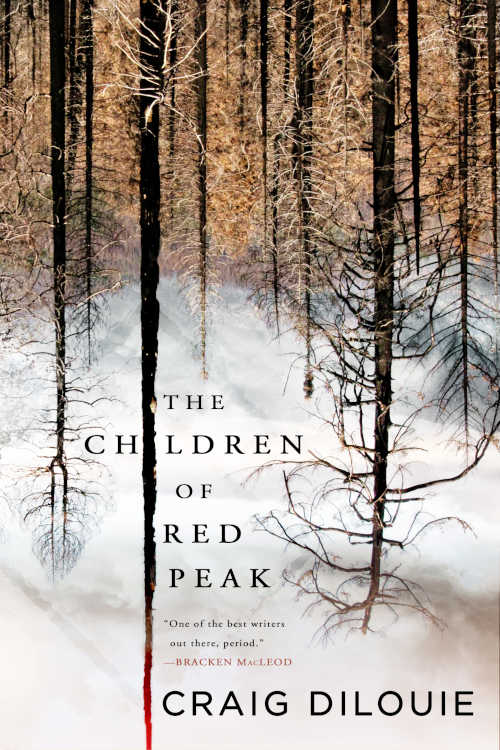

by Craig DiLouie

In the last issue of Books & Buzz Magazine, I described a journey I took to better understand the science of reading and what insights I could gain from it as a writer. I found the topic fascinating enough to keep going.

What about writing? What’s happening in our brains while we produce stories? What could I learn from this to be a better writer?

Writing and the brain

The process of creative formulation and physical writing lights up a whole lot of the human brain. Language, cognition, memory, visual processing, planning and control, and the ability to make associations between unrelated concepts all come into play. The prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, Broca’s area, posterior cingulate cortex, and hippocampus.

A small number of studies have looked at the concept of “story creation” and what areas of the brain might be involved. In one study from 2005 (Howard-Jones et al), participants were presented with a set of three words and asked to create a story based around them while getting a brain MRI. The researchers found activity not just in the brain’s language region but also the region responsible for making associations between unrelated concepts.

The popular perception is that writers are born with all their talent—and inspiration arrives like lightning, allowing the mad writer to crank out a great work.

In a later study in 2013 (Shah et al), participants were given thirty words, asked to brainstorm a story, and then given two minutes to write during an MRI. The researchers found activity in the region responsible for planning and control during the brainstorming.

Writers are born and made

Writers are born and made

One can’t consider the brain of a writer without wondering if there’s something different about it that makes that person predisposed to being one.

The popular perception is that writers are born with all their talent, creativity can’t be taught, and inspiration arrives like lightning, allowing the mad writer to crank out a great work.

The reality is that while creativity is a function of intelligence, the majority of people have creative problem-solving skills, and the actual skills involved in writing can be taught. Writers do not have to write in a vacuum, but can benefit from criticism as long as it is thoroughly constructive. Writing is hard work, and writers have more control over their work than might be felt during the process.

| MYTH | REALITY |

| Writers are born, it’s a natural talent | If you’re intelligent and have creative problem-solving skills, you can be a writer |

| Creativity can’t be taught | Creative skills can be taught |

| Writers work best alone | Writers can benefit from constructive, gentle feedback and reading other authors |

| Writers work best without convention | Craft can improve one’s game enormously |

| Inspiration arrives like lightning to produce perfect work | Many writers produce regular work, find writing hard work, and undergo a lot of revision |

| Writers are mere conduits for books to write themselves | Writers have a lot more control over their creativity than might be felt |

In fact, practice makes perfect, and writing is no exception, as borne out by research suggesting veteran writers have brains tuned for writing. If you’re like me, you’re a better writer today than you were last year, and not as good a writer as you’ll be next year.

In one study led by Martin Lotze, German researchers observed brain activity during the writing process and discovered that brain activity is different between novices and veterans. The brain activity of professional writers is similar in some ways to the brains of other skilled people like musicians or athletes, Lotze concluded.

In short, like a violinist who has to make a lot of racket before getting good, be prepared to grow as a writer by writing.

Writer traits

What else can we learn about how the writing brain behaves?

Fortunately for us, there has been an explosion of psychological research in this area in recent years. In one study, researchers at the University of California attempted to profile the psychology of the creative writer by evaluating thirty distinguished writers over three days in a “live-in” assessment.

Practice makes perfect. You’re a better writer today than you were last year, and not as good a writer as you’ll be next year.

They found five common traits: possessing a high intellectual capacity, valuing intellectual and cognitive matters, valuing independence, having high verbal fluency and quality of expression, and enjoying aesthetic impressions.

In another qualitative study, researcher Jane Piirto studied writers listed in the Directory of American Poets and Writers. She collected and analyzed interviews, memoirs, and biographies.

She, too, found five distinguishing traits: high levels of ambition (and envy!), high concern with philosophical issues such as the meaning of life, high levels of frankness and risk-taking, high value on empathy, and a keen sense of humor.

Yes, writers are awesome.

But … they’re also more likely to have certain mental issues.

Researcher A.M. Ludwig compared fifty-nine female writers to fifty-nine matched controls and found the writers suffered from higher levels of depression, mania, panic attacks, generalized anxiety, eating disorders, and drug abuse. Members of artistic professions, he found in subsequent research, were twice as likely to suffer from two or more psychological disorders as people in other professions.

At the same time, it is interesting to note that despite this, writers remain prolific, which is a sign of resilience, health, and strength of ego.

Fortunately for us, writing is also therapeutic. It’s commonly used as a therapeutic tool based on the premise that writing one’s feelings causes emotional trauma to fade, and self-awareness and self-development to grow. And it just feels good.

The flow

Now let’s get into the creative process. The process of writing is highly varied depending on the writer, but scientists have attempted to identify the stages in the creative process.

One of the most popular is the Wallace four-step process: preparation (gather information), incubation (subconscious works on ideas), illumination (make connection between ideas), and implementation (ideas become reality via critical thinking). To which creative frustration may be added (“Is this story working?”).

M. Csikszentmihalyi conducted a qualitative study of creative people, including prominent writers, who described experiencing “flow” during the process of writing. The writers described flow as a state of extreme concentration, challenge, skill, and reward.

SK Perry advised writers on how to get flow going. Be passionate about your project, get feedback, engage in preparation rituals—such as stopping work in the middle of a scene or sentence, allowing you to start again quickly next time—and minimize anxiety about a critical reception for your work.

I think that last one is a crusher—the fear nobody will like what you’ve created—necessitating very supportive and constructive feedback.

“A book,” Carl Sagan once said, “is proof that humans are capable of working magic.”

One way to get creativity flowing is to become exposed to others’ creative ideas. In one MRI study, thirty-one participants were asked to come up with alternate uses for everyday objects. Some of the participants were shown ideas of others, which resulted in increased neural network activity and subsequent greater originality.

For writers, this might mean reading the work of other authors, joining writing groups, attending writing conventions, and finding a constructive Ideal Reader.

Writer’s block

Sometimes, creativity doesn’t come easily and it’s hard to get into the flow. Writers call this “writer’s block.” But is this a problem of producing words, or of coming up with what happens next?

Some writers freeze up at that commitment because of fear or lack of confidence. Again, the sense that all this hard work will only lead to harsh criticism.

“Writer’s block is a highly treatable condition,” wrote Dr. P. Huston, University of Ottawa Heart Institute. “A systematic approach can help to alleviate anxiety, build confidence, and give people the information they need to work productively.”

Huston wrote a whitepaper on how to treat writer’s block. The document was aimed at academic writers, but I think it’s readily applicable to fiction.

Basically, Huston says if there’s a mild blockage, establish realistic expectations, allow yourself to be imperfect (write a draft), sidestep whatever is blocking you, and optimize your writing conditions. If there is moderate blockage, imagine you are someone you admire writing, talk through your work with a sympathetic ear, write stream of consciousness to prime the pump, or take a break. And if the blockage is severe, consider cognitive or behavioral therapy or imposing a system of negative consequences (such as an app where you have to give money to a charity you hate if you miss a writing goal).

Parting words

“What an astonishing thing a book is,” said scientist Carl Sagan. “It’s a flat object made from a tree with flexible parts on which are imprinted lots of funny dark squiggles. But one glance at it and you’re inside the mind of another person, maybe someone dead for thousands of years. Across the millennia, an author is speaking clearly and silently inside your head, directly to you. Writing is perhaps the greatest of human inventions, binding together people who never knew each other, citizens of distant epochs. Books break the shackles of time. A book is proof that humans are capable of working magic.”

Thank you for joining me on this journey to uncover the scientific foundation for this magic, which I hope you found as inspiring as I did.

Craig DiLouie is an American-Canadian author of speculative fiction. His most recent work is The Children of Red Peak, published by Hachette. Learn more about Craig’s fiction at www.CraigDiLouie.com.