When writing about mental illness, handle with care

Troubled by the depiction of mentally ill characters in popular novels, movies, and TV shows, this horror author has some tips for taking a more sensitive approach to the topic.

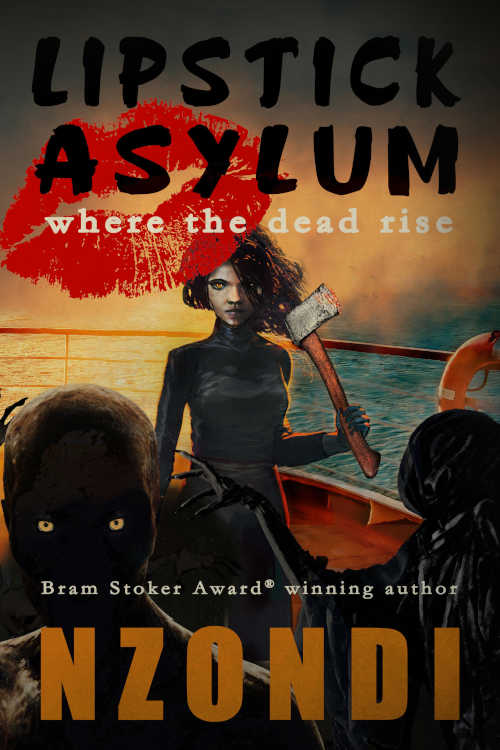

by Nzondi

In Heath Ledger’s Oscar-winning performance in his portrayal of Batman’s most notorious villain in The Dark Knight, he said, “As you know, madness is like gravity. All it takes is a little push.”

The film, the actor, and real life orchestrated a cacophony that sends a chill up my spine to this very day. When I used to run the ScHoFan Critique Group in the Greater Los Angeles Writers Society, I remember a time when I introduced a story with a suicide narrative. It was then that I learned how using the wrong language could trigger a negative response.

I never wrote that story, becoming aware that reinforcing certain stereotypes of people with mental illnesses was dangerous and could cause real-life discrimination, or worse, harm. There have actually been novels, which I will not name out of sensitivity to the subject, that led to a copycat effect that increased by more than 300% after one of those novels was published. That is a stunning number.

I never wrote that story, becoming aware that reinforcing certain stereotypes of people with mental illnesses was dangerous and could cause real-life discrimination, or worse, harm. There have actually been novels, which I will not name out of sensitivity to the subject, that led to a copycat effect that increased by more than 300% after one of those novels was published. That is a stunning number.

In this article, I’d like to discuss whether horror writers should start exploring how to develop characters with severe mental illnesses with fairer and more accurate representation, how writing certain stories actually increases copycat responses, and what stories are out there in the horror genres that chose to tread different paths of presenting mental illness.

Does the DC film Joker: Put On A Happy Face portray the character as a psychopath or a mentally ill person? The film creates empathy for the character, and portrays him as a person that has a difficult time dealing with an array of physical abuse. When the supervillain first appeared in the debut issue of the comic book Batman on April 25, 1940, the joker was introduced as a psychopathic prankster with a warped sense of humor.

Forensic psychiatrist Vasilis K. Ponzios, M.D., says, “There is still a misunderstanding to the portrayal of insanity in the Batman films and movies and what it means to be legally insane.” He goes on to say, “For instance, the Joker has been hospitalized at the Elizabeth Arkham Asylum for the Criminally Insane, even though in real life he probably wouldn’t qualify … Just because a behavior is aberrant … it does not mean the behavior is a result of mental illness.”

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders does not list insanity as a disorder. According to one article I read, hallucinations, delusions, and incoherent speech, which are traits of a severe mental disorder, are not usually the characteristics of a master criminal. Dr. Hannibal Lecter is the main character we all hate to love in a series of suspense novels by Thomas Harris. A brilliant and sophisticated forensic psychiatrist in the day, and a cannibalistic serial killer by night.

To my knowledge, the portrayal of that character was not diagnosed with a mental illness. However, iconic horror characters in the Halloween and Friday the 13th franchises play with the idea that psychopathic serial killers are mentally ill. Eventually, both characters are committed to mental institutions. In real life, these characters would be in a penitentiary, and/or on death row.

Reinforcing stereotypes of people with mental illnesses is dangerous and can cause real-life discrimination—or worse, harm.

So how can horror authors take a fresh approach to presenting attitudes of mental health issues? First, before I get into the next subject area of mental health, let me start by explaining exactly what I mean by the copycat effect (perhaps a better term would be suicide contagion).

Suicide contagion is the characteristics of media portrayals of suicide and characteristics of individual adolescents that increase the rate of suicide, and the magnitude of the increase is related to the amount, duration, and prominence of coverage. A news program may not be as negatively effective as a New York Times bestseller or a hit TV show on the matter. Dr. Madelyn Gould, PhD, professor of epidemiology in psychiatry at Columbia University, believes that indirect influence occurs in both real and fictional characters portrayed in the media.

One fresh approach that was bold and controversial was taken by creators of the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why, based on the eponymous novel by Jay Asher. According to the CDC, suicide is now the second most common cause of death among teens and young adults, accounting for nearly six thousand deaths annually in individuals between the ages of fifteen and twenty-four. I, for one, do not want to write a novel that participates in any mental health contagion. Therefore, seeing how 13 Reasons Why approached the issue is intriguing to me for my own writing.

For one, the executive producers, Selena Gomez and writer/producer Brian Yorkey, have gone above and beyond in showing their sincere motivations behind adapting the novel for Netflix. There’s a genuine sense of empathy for the subject matter. In the video portion of the teenlineonline website, the creator of the non-profit organization realized that when teens have a problem, they are more likely to go to other teens than to their parents. She set up a hotline using teen volunteers to help troubled teenagers address their problems. 13 Reasons Why resonated with teens because it was a story brilliantly told by young actors.

Hopefully, as horror authors, we can continue to scare the jeebies out of our readers while accurately portraying mentally ill characters.

13 Reasons Why tackled issues like suicide and bullying head on, yet still presented it in a way that got popular culture talking about these issues, which was the most important asset to helping real-life youths open up a dialogue with teachers, parents, and health professionals. In writing this article, I learned many things to do and not to do when writing about mental health issues. I recommend that all authors research these dos and don’ts before writing about any characters that have mental health issues.

As a horror writer, however, you may feel like your story is not there to preach, teach, or raise awareness. However, given the fact that there have been documented accounts of novels causing an increase in the rate of contagion, wouldn’t you want your literary themes to reflect a more accurate perspective?

Look, I get it. I’ve worked as a stand-in on a show called “How To Get Away With Murder,” and I have had many conversations with attorneys who say that the show is too sensational, especially in the courtroom. I’m like, “Thank goodness the creator of the show doesn’t depend on you to write their episodes. We’d be bored out of our minds!” They are the same people who can’t suspend disbelief long enough to get past the fact that when Bruce Banner changes into the Hulk, he’s always in those purple short-pants, instead of being nude.

We are writing fiction, aren’t we? We create a way for the reader to escape reality and travel to worlds of fantasy, science fiction, dystopia, and horror. Still, when writing about characters and stories involving mental health, shouldn’t we ask questions that breathe life into the “who, what, when, and how” of the tropes we use?

So how do we get it right?

Here are some facts to know about mental illness by Kathleen S. Allen, an author who also has a Doctor of Nursing Practice degree (which is a clinical doctorate):

- Having depression doesn’t mean your character can’t still have fun or laugh or be social.

- A character who has bipolar disorder may have manic episodes or they may not. Bipolar disorder has a spectrum of symptoms from moderate depression to severe.

- No one who has Dissociative Identity Disorder (formerly called split personality) would kill someone when they are in one of their alter personality states unless the core personality would also kill.

- Your character would not have amnesia after killing someone. The disorder is rare, and some medical professionals don’t believe it exists at all, so be careful using it.

- Talking about suicide does not mean your character will push the person into attempting suicide. It was already on their mind.

- Your characters don’t stop hearing voices immediately after taking anti-psychotic medication.

- Sometimes, they won’t stop at all. It may take weeks to months for the meds to work. If they are having a psychotic episode, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to function in their daily lives by going to school, work, maintaining a romantic relationship, or maintaining any relationship. Psychotic patients are not dangerous. Are there exceptions? Yes. But as a general rule, they aren’t.

- In conclusion, one of my biggest takeaways from researching horror writing for Mental Health Awareness Month was some of the things we shouldn’t do.

- For example, unless your character is politically incorrect, don’t describe suicide as an “epidemic”, “skyrocketing,” or other exaggerated terms.

- Use words such as “higher rates” or “rising.” Don’t describe suicide as “without warning” or “inexplicable.”

- Do convey that the character exhibited warning signs.

- Don’t refer to suicide as “unsuccessful” or “failed attempt,” or report it as though it were a crime. Do say, “died by suicide,” “killed him/herself,” and instead of presenting the act like a crime, write about suicide in your story as a public health issue.

Hopefully, as horror authors, we can continue to scare the jeebies out of our readers, but at the same time, create a story which accurately exhibits archetypes of mentally ill characters, whether they are mad scientists, psychopathic serial killers, or characters with dissociative identity disorders that assume their mother’s personality.

Nzondi (Ace Antonio Hall) is an American science fiction and horror author. His novel Oware Mosaic won the Bram Stoker Award for Superior Achievement in Young Adult fiction, the most prestigious award given to horror writers in the world. He is the first African-American to win in a novel category, including the YA novel category.

A former director of education for NYC schools and the Sylvan Learning Center, the award-winning educator earned a BFA from Long Island University. Nzondi is currently bi-coastal, living in New York and Los Angeles.